At High Mill, Verdant Works Dundee, November 2015 (Living Field)

…. more

sustainable croplands

At High Mill, Verdant Works Dundee, November 2015 (Living Field)

…. more

A sculpture at the William Ricketts Sanctuary, Dandenongs, Victoria, Australia. More … here.

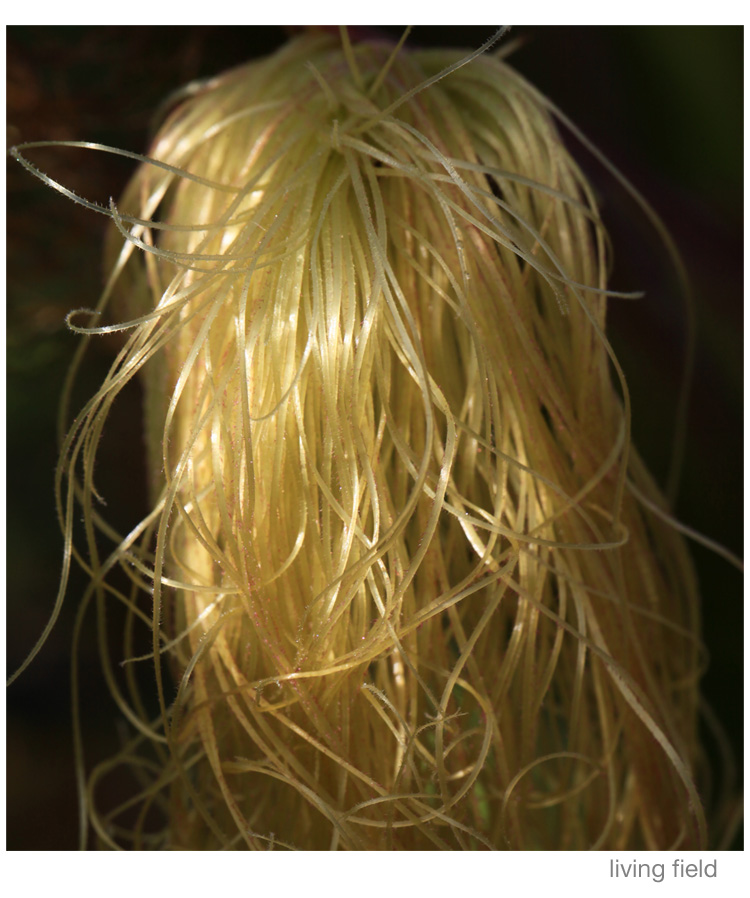

Sections down a single maize silk, the upper one just below the exit from the forming cob: each strand, less than 1 mm wide, leads to a seed site deep in the cob, 23 September 2015, Living Field garden (Living Field collection).

Bad hair day ….?

A newly formed silk … but too late in the year for success, 23 September 2015, Living Field garden (Living Field collection)

See also: Fiberoptic 3, Fiberoptic 2 and Fiberoptic.

Bere and barley both named in Andrew Wight’s journeys of 1778-1784. Bere as the substrate for aquavitae. Bere as a nurse for grass. Bere seed maintaining its mass to volume ratio. Bere fertilised with seaweed.

A note in the Living Field’s Bere line …..

Andrew Wight, a farmer from East Lothian was commissioned to undertake a series of tours in the late 1700s to examine and report on the state of agriculture in Scotland. His work was published anonymously between 1778 and 1784, but is invariably referred to by his name, and quite rightly, since it was a major undertaking and the best single guide to the state of agriculture during the long ages of improvement (reference below).

He travelled by horse to mainland areas, meeting farmers, tenants and landowners and noting the improvements, or lack of them, to husbandry .

Throughout he refers to both barley and bere, sometimes in the same place, which suggests he considered them different things, presumably bere being the 6-(or 4) row types and barley the 2-row.

He related many anecdotes about bere. Here are a few of them on the journey north from Inverness to Sutherland.

He visited the area around Ferintosh, on the Black Isle, owned by Forbes of Culloden. Ferintosh was …. “famous for the great quantities of aquavitae made there under exemption from duty. I am told that there are no fewer than 1000 distillers in that place, wholly occupied in making spirits, utterly neglecting their land, which is in a worse state than for many miles around”. He goes on to write “great quantities of bear are imported from the neighbourhood, and malted there as Ferintosh bear: Not only so, but quantities of aquavitae made elsewhere are carried to market as Ferintosh”. [Ninth Survey Vol IV.I, p. 238].

Of those areas supplying the distilleries was Fowlis, which ‘ .. near the Cromarty Firth has access to seaweed and lime is imported from Portfoy … and bear finds a ready market at Ferintosh.” [p 239]

So you can imagine all these bear harvests from all around, going, not into mouths of people and animals as meal, but to distilleries at Ferintosh, and whisky coming out for export; and everyone so involved in making the stuff that the land went to waste.

But these days bear grain contributes to only a few specialist malts. Most are made from two-row barley.

Wight implied that exemption from duty was granted as a monopoly to that particular estate before the Union, and became ‘destructive to fair trade’ and ‘the occasion of manifold frauds’. Back-handers and dodgy labelling – what’s changed? But the distillery went out of business in around 1785, presumably because other distillers complained abut the unfair exemption.

At Invergordon, he writes …. ‘Wheat on this strong land was very good; barley after turnip excellent; beans and pease are never neglected in the rotation; oats in their turn make a fine crop; but above all, the old pasture excels. Later, at the same place, he tells of a method used to protect new-sown grass pasture.

The farmers anticipated a demand for hay or grazing the next year that current grass fields could not supply. So what could they do? They could sow more grass late the present year (September), but what could be done to avoid the seedling grass being damaged over the winter. The solution was to sow grass (which then included various legumes and ribwort plantain with rye-grass) and then … he related….

‘Three firlots of bear were sowed at the same time upon the acre, intended as a cover for grass during the winter …… The bear grew vigorously, and covered the surface during the severe months, but died away on the approach of warm weather.’ The bear seed was sacrificed, it seems, to solve the problem ‘when grass-feeds must be sown in the wrong season’. [Ninth Survey, Vol IV.I, p. 248-250]

Repeatedly, the writer points to farmers who use lime or marl to reduce acidity, and dung to replenish nutrients taken from the soil by previous crops. Soil fertility was probably the major limitation to maintaining yield.

At Lochbeg, Sutherland, about Mr Gilchrist, the proprietor, he writes “His mode of cropping is one half (the land?) under bear, manured with sea-weed, which is spread on the ground directly, and mixed with soil in spring in two ploughings. Three firlots sowed yield seven bolls per acre.” [Ninth Survey, Vol IV.I, p 307].

On the Route Homeward, he calls in at Castle Grant. “One thing is extremely remarkable with respect to bear on this farm. Though, time out of mind, no feed has been used but what is produced in the farm itself, yet it never degenerates. To this day a boll of bear, measured by a firlot of 32 pints weighs 20 stone Amsterdam’. And he goes on to write that it degenerates every where else after three or four years sowing, ‘Yet this country lies high, and the climate is cold and stormy.’

An uncertainty in interpretation here seems to be what is meant by the word ‘degenerates’. All cereal harvests consist of grain (seed) that is used for food or sale and the supporting and protective ‘stuff’ around the grain – the stem, the spiky awns, the coverings. A good harvest has a high proportion of grain to all the rest. But grains will only grow to their full extent if they have enough nutrients from the soil.

We have noticed in the Living Field Garden, where bere and other cereals are maintained by saved seed, that the plants might put out all the supporting and protective materials, but if nutrients are short, then the grains do not fully fill. The resulting harvest is not heavy per unit volume of material.

A crucial feature of the bere on the estate that Mr Wight refers to seems to be that the ratio of volume to mass of grain (firlots to Amsterdam stones) is maintained over time. The heaviness does not decline presumably because soil nutrients removed by the crops are replaced by nutrients from elsewhere on the farm and this happens ‘time out of mind’.

This may be a case of highly effective, scientific, nutrient management centuries ago – before labs, remote sensing and intelligent machines.

And he writes a farewell to Volume IV.I: “Having now no ground to survey, and having been long out, I proceeded with the utmost expedition homeward, to make up the loss that my absence occasioned in my private affairs.”

Many thanks Mr Wight!

[There will be more from Andrew Wight in future notes on the Bear line – rhymes with hairline].

Wight, A. 1778-1784. Present State of Husbandry in Scotland. Exracted from Reports made to the Commissioners of the Annexed Estates, and published by their authority. Edinburgh: William Creesh. Vol I, Vol II, Vol III Part I, Vol III Part II, Vol IV part II, Volume IV Part II. All available online via Google Books. With thanks.

Ayrshire in the age of improvement. Contemporary accounts of agrarian and social improvement in late eighteenth century Ayrshire. 2002. Edited by David McClure. Published by Ayrshire Archaeological and Natural History Society. [The introduction gives background to Andrew Wight’s mission and journeys.] Available online.

See also on the Ferintosh Distillery (closed 1785): lost distillery.com/06ferintosh/ryefield.html

For a growing list of bere notes, articles and recipes on this site: Bere line …

Throughout August, wet ditches and banks and boggy corners are filled with wild plants in flower and host to many types of insect.

Many of these plants have at some time or another been used in medicinal preparations – meadowsweet Filipendula ulmaria for fevers, and with willow the source of precursors of aspirin, valerian Valeriana officinalis as sedative, wild angelica Angelica sylvestris as condiment and cure-all, sneezewort Achillea ptarmica to clear a blocked nose, hemp-agrimony Eupatorium cannabinum for ‘catarrhs and coughs’ and yellow iris Iris pseudacorus whose uses are so wide-ranging that one alone can’t be mentioned.

Hardly valued now, they still offer rich findings to those who wish to explore our botanical heritage.

The roadside bank and ditch above, in Strathnairn, holds, within a three metre length, all the herbs mentioned here except hemp-agrimony. Sneezewort is growing at the front on drier ground. Lower images, floral branches of meadowsweet (right) and angelica, each home to many insects.

These plants thrive where the surrounding vegetation is semi-natural or else grazing land having few or no inputs of mineral fertiliser.

Elsewhere, the runoff from well-fertilised arable or grass encourages aggressive and dominant weeds – willow herb, thistles, nettle, docks and the sprawling cleavers – that soon oust the more delicate and slower growing.

The Living Field garden grows all the medicinal plants mentioned here, but for garden angelica rather than wild angelica.

Sources for medicinal uses: Grigson G 1958, 1975 An Englishman’s Flora. Darwin T 1996, 2008 The Scots Herbal. Plants for a Future www.pfaf.org

[Live on 16 September 2015]

Unremitting wet since solstice-time in late June. The field scabious Knautia arvensis offers bee-food en masse for months in most years, and in June the mauve flowers promised a fine show, already thick with bumble bees.

Since then they have been thrashed by the heavy rain and wind and grasses now dominate the meadow. Yet on the rare sunny afternoon, the insects take their feast on the Garden’s wild plants.

Chief among them are the nitrogen fixing legumes, offering high-nitrogen, high-protein take-away. The images (above, top left clockwise) show white melilot, the blue-flowered tufted vetch, sainfoin, alsike and lucern.

Only the tufted vetch is common in the margins and lanes here. The others have been tried as forages in the past but are now rarely found. Other legumes flowering (not shown) include red and white clover, the yellow-flowering melilot and greater bird’s-foot-trefoil, all well attended by bees.

The other plants that most years offer months of rich flower-food fare no better.The striking, blue viper’s bugloss in the medicinals bed is almost finished bar a few, one of which is shown above right. And the remaining field scabious, bottom left above, will continue to put out their sumptuous floral parts for bees to drain and trash.

Yet again, the benefits of growing in this small space a diversity of native and medicinal plants pays, because teasel, knapweed and greater knapweed, and a set of annual composites including cornflower and corn marigold are all offering their wares in return for chance pollen.

Teasel will now flower along its bristly head for some weeks – the ladybird in the image top left above just slotting in between the spikes, jostling several aphids that may not be visible at this magnification.

What’s to come – the deadnettle family – the labiates – will sustain the insects through to the autumn equinox. Many are only just in flower – betony, wild marjoram, some field mints, hemp-nettles, a calamint, sage, lemon balm and hyssop.

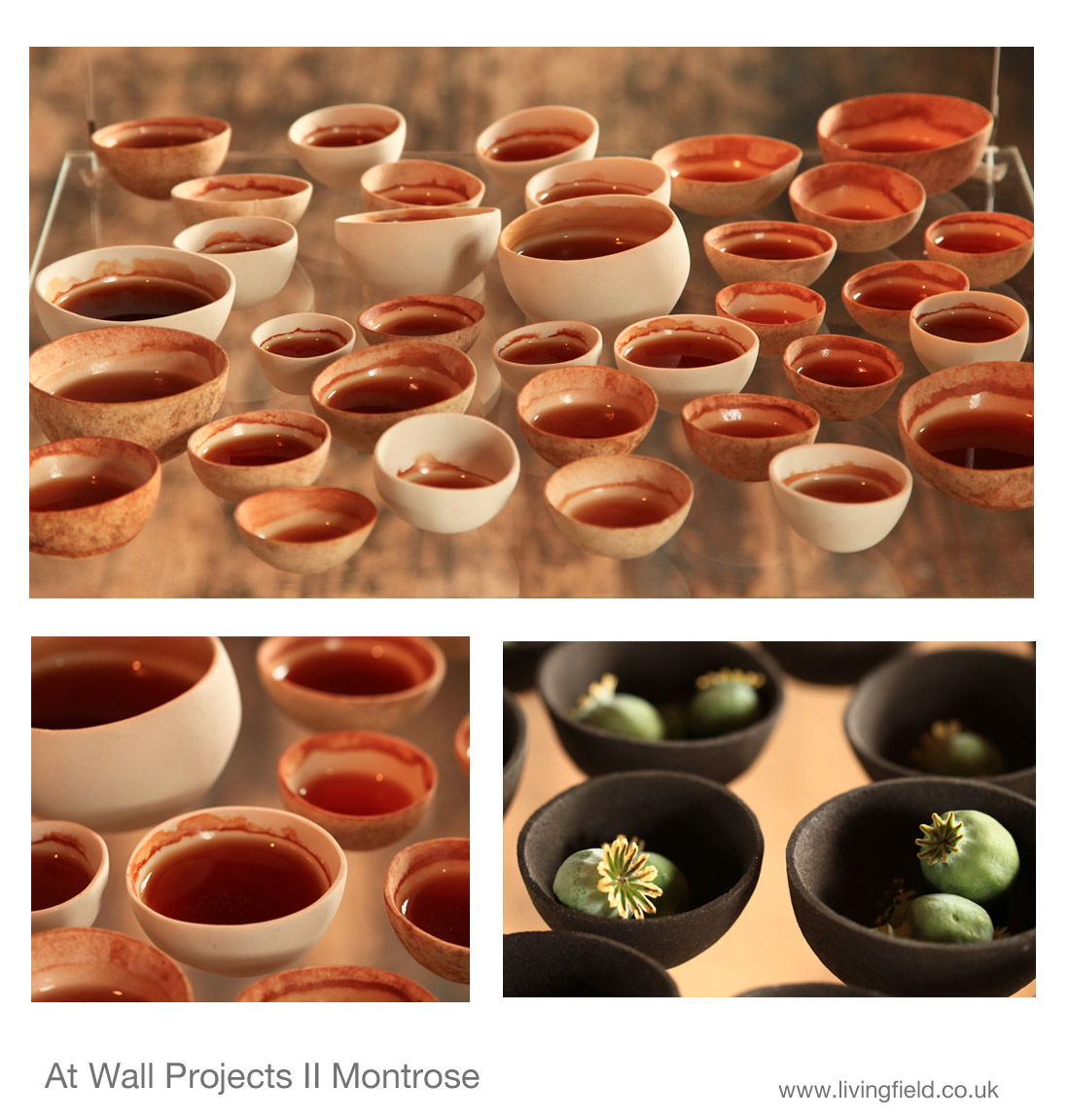

This fine exhibition, on themes of Empire, is housed at Wall Projects II in the Old Ropeworks off Bents Road in Montrose. The venue itself is a work unique, including an upper room (image below) and the very long and narrow rope works on the ground floor, disused and part derelict and now open in places to sun and rain.

Dark in parts, this exhibition: it makes you think of how ordinary people become complicit in dire trades and livings, in buying and selling people, in slavery on a massive, organised scale.

Here’s the earner: sail to european ports with some good local Scottish produce like salmon, textiles and things to smoke; offload the cargo – but an empty ship costs money – so off down to Africa to fill up with slaves; take them to the Americas, leave them there to be sold and worked; then bring back tobacco. Scottish enterprise! So tells the audio exhibit Considered Cargo by Carolyn Scott.

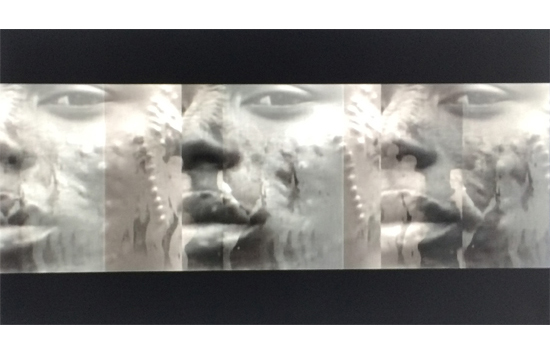

The dehumanising of peoples considered little more than zoological specimens continues in the utterly mesmerising four-minute video Shadow Show by Kyra Clegg (an image captured above by K Squire).

Other artists tell of the whale trade, the driving to near extinction of these great, warm blooded, social mammals; the realisation that they individually suffer. Linen, whale oil, jute, slaughter, wealth inextricably linked.

It’s not all dark – there is lightness and humour among the twenty artists exhibiting here, but threads recur of claim and exploitation.

Take the insidious link between beverage and narcotic, tea and opium, Camellia sinensis and Papaver somniferum, a leaf-stimulent drunk by most people in Britain and the poppy-head-latex source of the heroin trade. Those Europeans who like tea, should perhaps know its origins. But no blame to the tea plant, and no blame to the poppy for it also gave us one of the best painkillers.

At the farthest end of the rope works is an impenetrable mass of ivy roots, hanging down, and from them (or to them if you look the other way) stretches the orange to yellow to grey to black complex curve of coloured, filled balloons in Meltwater by Juliana Capes. It’s the seasons played out.

We spent some hours at Empire. Sorry not to mention all the artists exhibiting, but go and see for yourselves. One of the very best.

Empire by the Society of Scottish Artists, at Wall Projects II, 13 Bents Road, Montrose, Angus DD10 8QA. Various dates to 29 August 2015. Check the web site : www.wallprojectsltd.com or email kimcanale@wallprojectsltd.com

Society of Scottish Artists web page on Empire has many photographs of the exhibits and notes about the artists: http://www.s-s-a.org/empire-at-wall-projects/

The restharrow Ononis repens is a tough plant, growing as it does at the very limits of dry, salty land around the coast. There it will fix nitrogen from the air, which finds its way through decomposition of roots and leaves into the sand and then perhaps to other plants and to soil microbes. It was also once a serious weed of cropland, as its name suggests, but a weed no longer, tamed by heavy ploughs and pesticide.

It grows well around the coasts of Angus and Moray. In Montrose bay, it grows in abundance, the main legume of the dunes. It is prolific near the south end, particularly around the car parks, binding the sand as it once slowed the harrow. To the north over the several miles of beach, it lives at the base of the collapsed dunes (images above), leaf and flower blasted by salt and sand grains.

In the images above, the line of stakes leading seaward from the dunes reaches out into the North Sea at its widest and after 650 km of rough water, meets the coast of Denmark. The restharrow is the first line of defence.

Grigson gives the mediaeval names of the plant, one of which resta bovis translates as ox-stop, and cites a treatise of 1578: ‘the roote is long and limmer, spreading his branches both large and long under the earth, and doth ofttimes let, hinder and staye, both the plough and oxen in toyling the ground’.

In her 1920 book, Winifred Brenchley classed restharrow Ononis repens among ‘coarse growing plants that deteriorate the quality of pasture or meadow’. And in the last century it seems to have been a problem in grass rather than in land that was repeatedly tilled.

Its decline from the community of common weeds is now so great that it is hardly found in farmland. Yet as recently as 1938, H. L. Long wrote “If this weed is plentiful it must be attacked by thorough and regular cutting, liming, complete manuring, and close depasturing with stock. In rare instances it may be desirable to plough up the pasture, give a thorough cleaning and manuring, and again lay down to grass.”

Long placed it in the top 30+ weeds of pasture, but did not always distinguish the spiny Ononis spinosa, which has a more southerly distribution in Britain, from Ononis repens which is the one shown here in the photographs and which was described by Long as having runners, usually spineless and with a strong disagreeable scent.

Grigson relates its presence in pasture as tainting milk, butter and cheese and children chewing its root, which gives it the name wild liquorice.

A few patches of restharrow remain in a remote corner of one of the Institute’s farms near Dundee.

To see what it looks like and how it grows, the Living Field garden keeps a small patch of it, originating from seed. Its luxuriant foliage and flowers grow to well over 0.5 m in height and attract a range of insect feeders. It is cut back to 10-20 cm above soil level in autumn, but is otherwise left to itself.

Its leaves and stems are softer in the garden, less wiry than at the edge of the North Sea (comparison above). There are also small variations in geometry of the leaves and sepals.

Brenchley WE. 1920. Weeds of farm land. Longmans, Green and Co, London. Grigson G. 1958. The Englishman’s flora. (Paladin, 1975). Long HC. 1938. Weeds of grass land. HMSO.

Note: on sampling the coastal plants, Euan James reports nodulation, indicating they are fixing nitrogen.

Contact/date: GS 30 July 2015.

Also on the web site: