First in a series on nitrogen fixing legume plants.

Legumes are a group of plants that ‘fix’ nitrogen gas from the air to make proteins that are essential for growth and survival. When legume tissue dies, the nitrogen (N) is returned to the soil.

Legumes have many uses to people as food, medicinals and dyes. They also support insects that in turn carry out ecological functions such as scavenging and pollination.

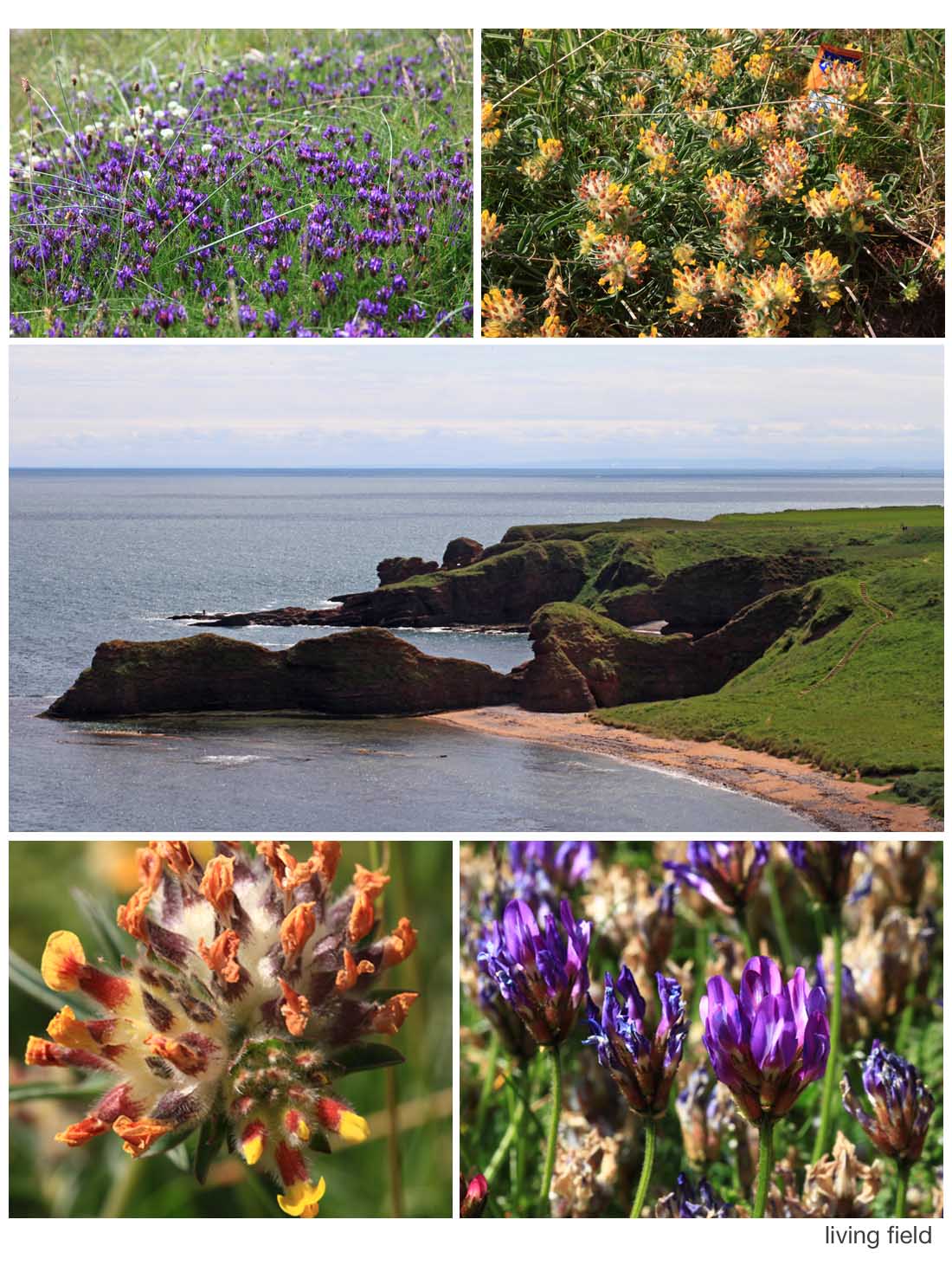

Here we begin a short series on wild N-fixers. First are those that live by the eastern shores of Angus.

The east coast of Angus (middle image) is rich in wild legumes. Those shown here live just above the beach or on top of the cliffs, where the vegetation is short and there are no bigger plants to out-shade them. Top left is a patch of purple milk-vetch Astragalus danicus and white clover Trifolium repens behind, top right kidney vetch Anthyllis vulneraria with litter, and ( bottom) flowering heads of kidney vetch (left) and purple milk vetch.

Nearby were patches of meadow vetchling Lathyrus pratensis, bird’s-foot-trefoils Lotus species, and on the cliff-tops bush vetch Vicia septum, gorse or whin Ulex europaeus, broom Cytisus scoparius and the introduced laburnum Laburnum anagyroides.

One reason for the presence of legumes here is an unfarmed habitat, low in nitrogen. Fixation by the legumes is one of the main routes by which the plants and soils get their essential nitrogen.

Most of these wild legumes have been tried over the last few thousand years as crops or forages. Some such as kidney vetch have been well-know medicinals (a vulnerary is a herb for treating wounds). Few have remained useful to agriculture, perhaps the best known being white clover, still cultivated today to enrich grass fields with fixed nitrogen.

Legumes are of the pea family Fabaceae, previous known as Leguminosae.

Related on this site:

- Kidney vetch and the small blue

- Fixers 2 – restharrow

- Fixers 3 – crimson clover

Contact: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk