Most of our paper comes from plants, but the process by which leaves and stems are converted to sheets that we can write on or wrap things in is unknown to most of us.

As part of her work with the Living Field, Jean Duncan has been making paper from plants grown in the garden.

She started with some maize, which is a tropical and sub-tropical species originally from the Americas. Some types can now grow in our climate, and it was one of these that was grown in the garden for its cobs (corn on the cob).

Jean used the maize plants to make the paper. Here is a description of what she did.

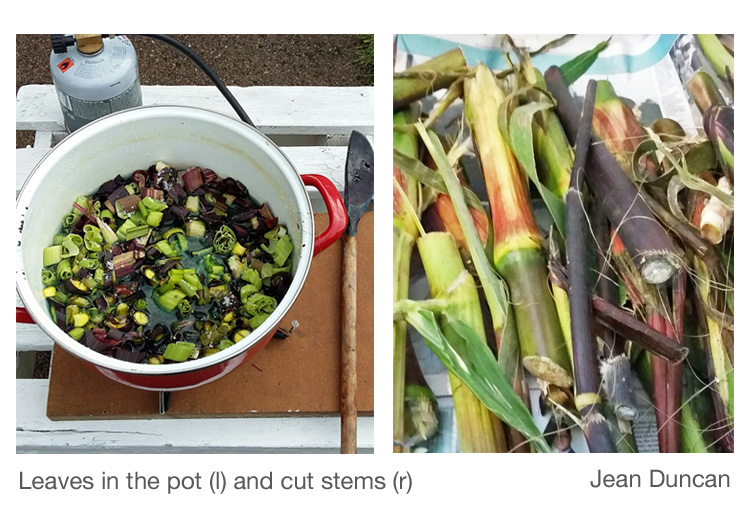

Step 1 is to collect maize leaves and stems when they are in good condition, still green.

Step 2 is to cut the leaves and stems into small pieces. Leaf pieces should be about the size of those in the white bowl. The tough stems were cut into larger pieces (right below).

Step 3 – put the cut material into an enamel bowl or pot (above left). Add soda ash to the material, 1 teaspoon for a 10 litre pot, and mix.

Step 4 – cook the plants for 3 hours, or more if the material is tough. At this point you will need pH indicator strips (litmus paper) to check that the cooking is going according to plan. (Litmus can be bought on-line or at some gardening shops.) The pH of the mixture should be around 8, but if it drops to 7 or 6 then add a little more soda ash. When cooked, the fibre should be soft and easy to tear.

Step 5 – rinse the fibre thoroughly in water; when fully rinsed the pH or the water should be neutral (i.e. about 7).

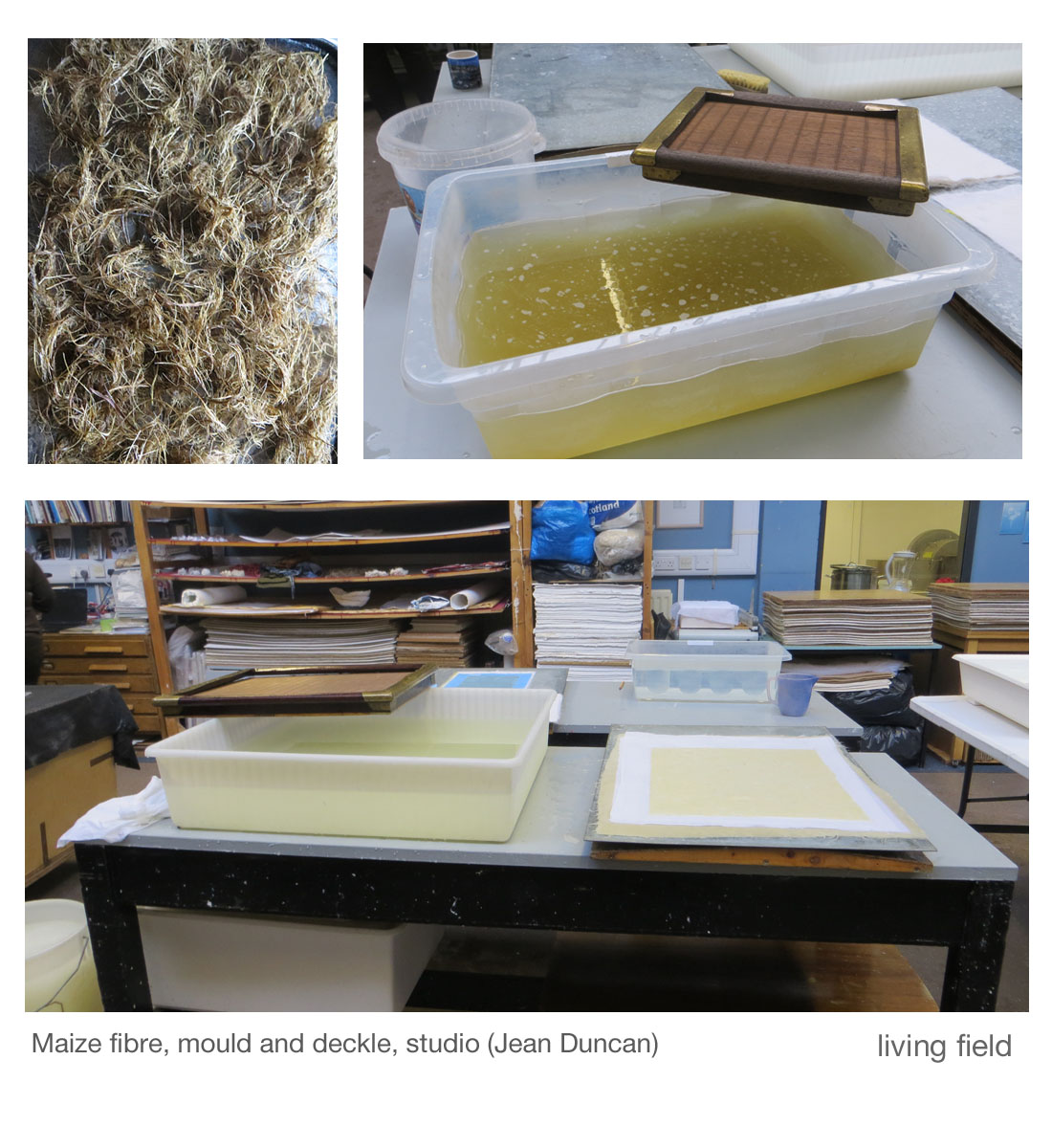

Step 6 – the fibre now needs to be beaten to a pulp. The traditional way is to beat it with a mallet for a few hours. (Craft-workers in some countries still use this method). An alternative, if you have electricity, is a kitchen blender working in short bursts so as not to burn out the motor. Jean uses a machine called a Hollander beater.

Step 7 – the fibres are now ready to be transformed into sheets of paper. The pulp is suspended in water. A ‘mould and deckle’ is lowered into the water (image above) and brought out slowly with a flat layer of fibre on it, or else the pulp is poured into the mould and deckle until there is a flat layer of the right thickness for the type of pulp (which you work out by trial and error); the water drains out through holes leaving the moist fibre.

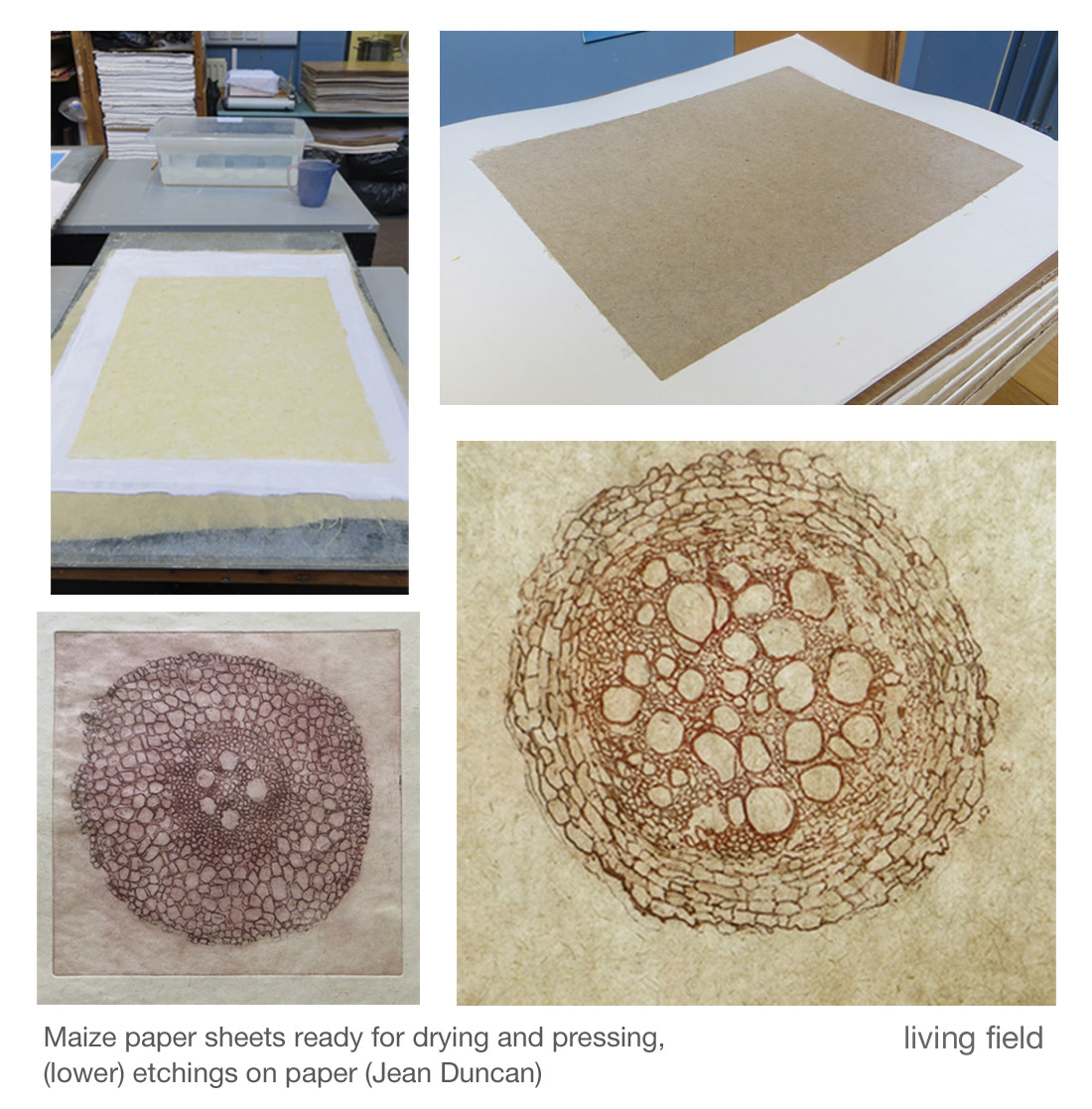

Step 8 – the moist sheet of fibre is turned onto an absorbent fabric or board or something similar for drying and pressing, a procedure that takes about 3 days (top right in images below).

And that’s it – a sheet of paper!

Info, links

Khadi papers India. Web site: khadi.com. Youtube: Papermaking at Khadi Papers India

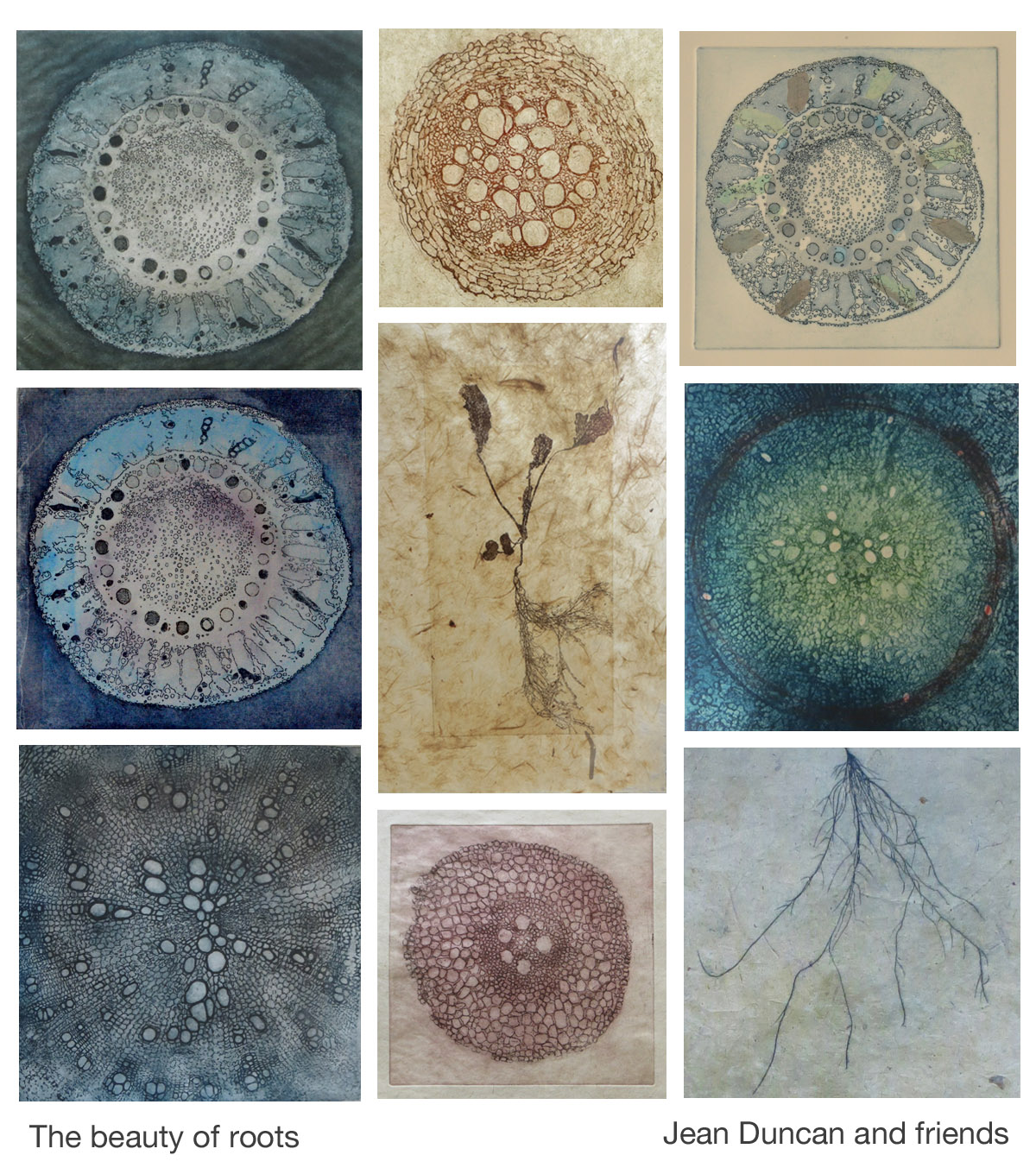

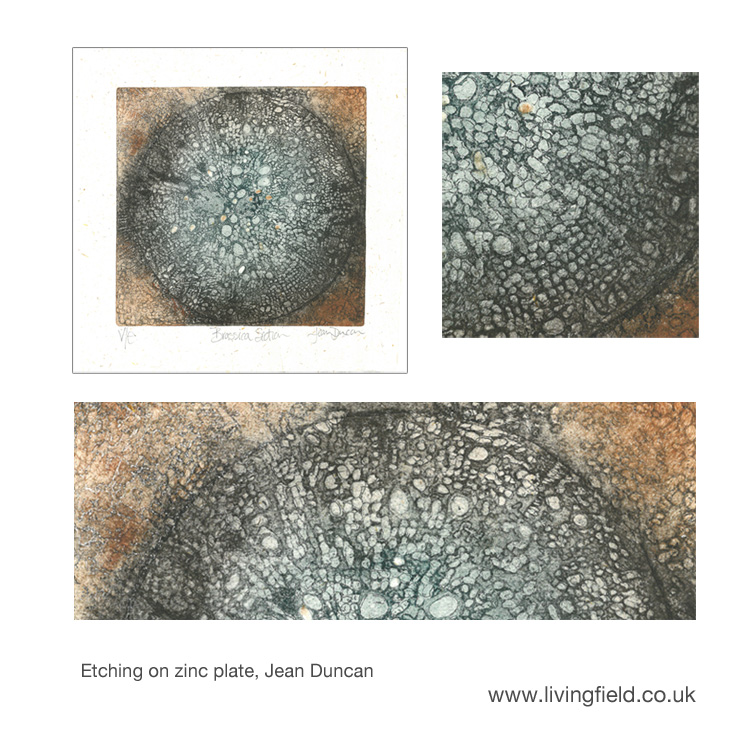

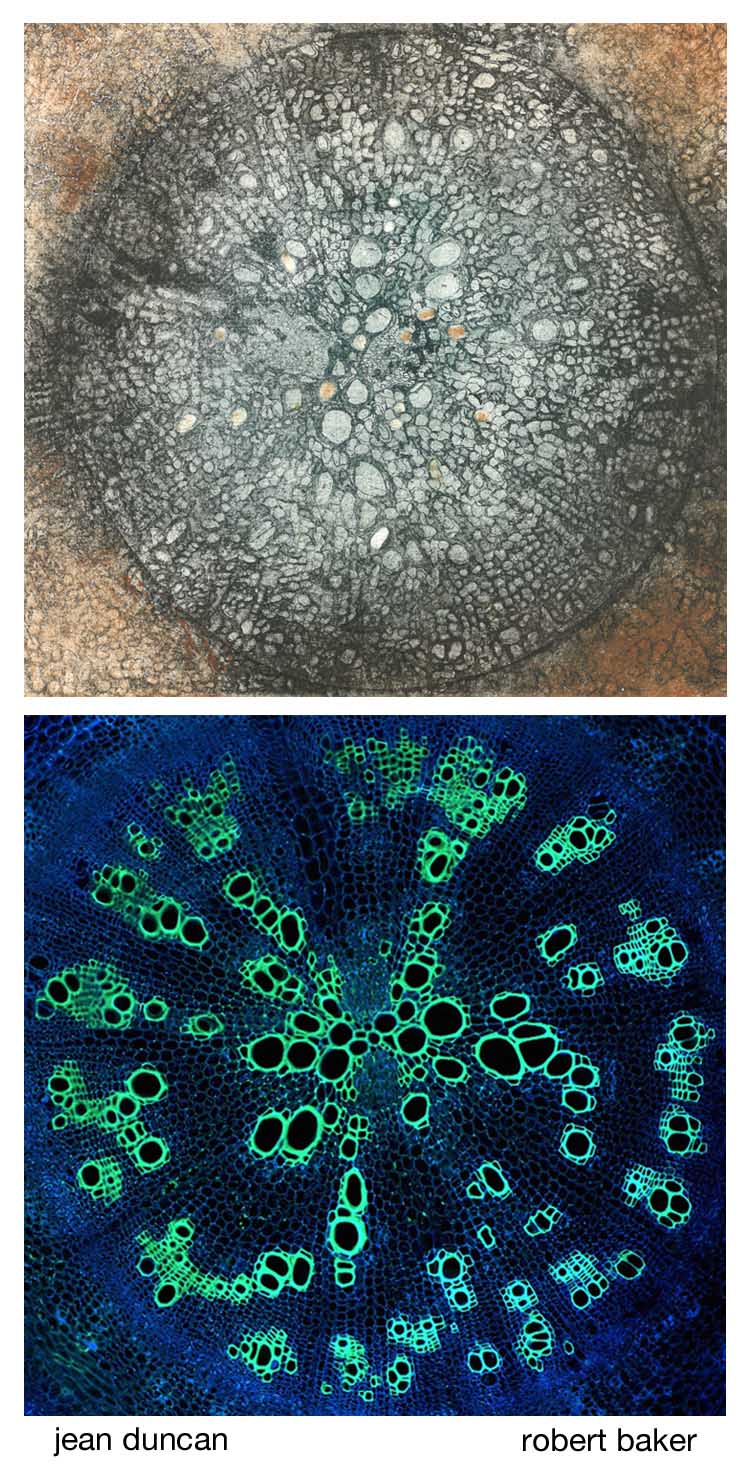

Jean’s recent work on an exhibition of etchings using her own-made paper: The Beauty of Roots and Root art.

[Update with minor amendments 10 June and 27 July 2017]